Kevin Lynch Interview: “Everything gets changed.”

I was doing a search that I sometimes do on Google, “Kevin Lynch video,” and the internet responded, for the first time, with a hit. The planner, writer, and thinker about cities is a hero of mine. I’ve written about him often and his influence on me and on the planning profession and practice in general. The Southern California Institute of Architecture has posted an almost hour long interview with Kevin Lynch videotaped in 1980 after Lynch had achieved notoriety in the planning world. I can’t embed the video, but you can connect to the SCI page here.

The interview is worth watching if you are a planner or just interested in the views of one of the most influential planners in the last half of the 20th century. First of all, I recognize that Lynch and I would probably have some good arguments about market forces and development. Lynch starts the interview covering his childhood and youth as part of an old Irish Catholic family in Chicago “wrapped around the questions of socialism . . . in the United States.” Lynch says that one of the most important events that shaped his early views was the Spanish Civil War, a conflict between Nationalist and Republican forces that became an international struggle between forces of Fascism and Socialism.

He got interested in architecture because of a 7th grade teacher that encouraged him to study ancient Egyptian architecture. He ended up going to Yale which he found to be too conservative; he said he “got disgusted and left.” He went on to study with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin for a year and a half before leaving after feeling “swallowed up” in the great man’s shadow. Wright wasn’t happy at the young Lynch’s departure, and Lynch describes how Wright cursed at him for leaving.

There is a lot more great stuff in the interview and I won’t ruin it by describing it all. But one gets a palpable sense of frustration in Lynch in the interview, and not just because of the interviewer (who can be heard saying “wow” at one point). Lynch was a seminal thinker in urban planning because he saw that planning was not an isolated academic or aesthetic exercise, but a powerful social, economic, and political tool capable of dislocation of people but also allowing them to have “more meaningful lives.” But it seemed like he felt too often the work of good planning was squeezed by government and market forces.

Today, Lynch’s ideal of including the public in planning seems obvious. And of course planning is political and social. But these ideas are accepted as a fact largely because of the work of Lynch and others to transform planning from government bureaucrats drawing vast boulevards on easels in government offices to engaging with actual people and residents to understand how their city works. He points out in the interview how a plan for new government office started out one way but ended up entirely something different. “Everything gets changed,” Lynch says over and over again in the interview, and he seems to think that’s a good thing.

Lynch believed in listening to neighborhoods because he thought engaging them would lead to better cities. At one point in the interview he says:

The most interesting movement in planning today is that of neighborhood planning; that it’s been mostly a reaction against disaster, you know, against an expressway or redevelopment or what have you. But we’re beginning to see a resurgence of the neighborhood in this country and it’s beginning to move from just a negative, a veto against things into positive action and positive planning.

As I pointed out in a recent post, neighborhood planning ain’t what it used to be. Somehow Lynch’s dream of planning becoming a part of a healthy part of the democratic process went wrong. Today, in Seattle at least, we have litigious and petitioning neighbors determined to stop growth and change even going as far as to propose moratoriums on growth and new housing. What’s next, sending new jobs to Bellevue. Ummm, well, yes. I think if Lynch saw what many neighborhoods are doing today, he’d see it as undemocratic, closing down the future in favor of preserving the past for a small group of people who happened to have gotten here first.

Image from MIT

Want To Help Preserve Existing Low-Cost Housing? Build Density.

When change occurs as rapidly as it has been in Seattle, misplaced blame runs rampant. And one of the most egregious examples is the contention that the construction of new housing is the cause of declining affordability—case in point, a coalition of Seattle neighborhood groups is currently advocating for a moratorium on new housing construction. But the reality in Seattle couldn’t be any more diametrically opposed: Building housing at higher densities is actually a means to reduce the loss of existing low-cost housing.

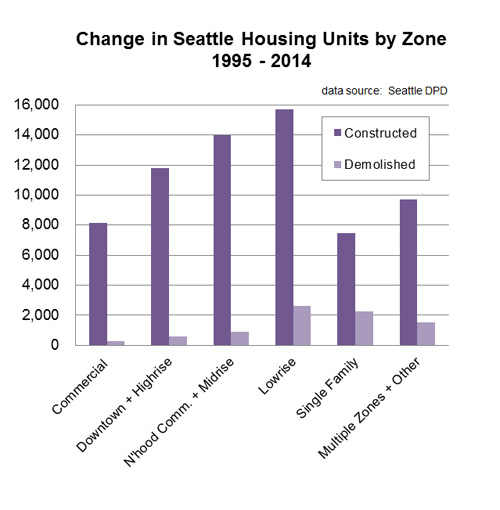

To understand why, start with the data. According to the Seattle Department of Planning and Development, from 1995 to 2014, 68,433 new housing units were built, and 8,724 units were demolished. That corresponds to a ratio of eight, meaning development is staying way ahead of the game in terms of net increase in housing, which helps affordability across the board by absorbing demand.

Furthermore, a nontrivial chunk of the demolishing likely had nothing to to do with housing redevelopment—the 8,724 includes units demolished for any reason, not just to make way for new housing. During 1996 to 2005 (newer data unavailable), over 25 million square feet of non-residential floorspace was developed in Seattle, and it’s reasonable to assume that some of that resulted in demolished housing. It is also reasonable to assume that some housing was demolished simply because the buildings had aged beyond their lifespan.*

While there is no question that housing development results in a lot more housing units gained than lost, it is also true that new housing is typically more expensive to rent or buy than old housing. And if new housing actually does take out existing housing, then the new units will likely be more expensive than the units that were lost. First, as alluded to above, to some extent this process is normal and cannot be avoided, because housing ages and eventually has to be replaced.

But second, and more importantly, it is a logical fallacy to conclude from this that housing development is inherently bad for affordability. Accurately assessing the impact requires a comparison to what would have happened absent the new housing. And in a high demand market like Seattle, the result would be greater competition for a limited supply of existing housing, which would drive up the rents, likely leading to renovation to meet demand for higher quality units. In other words, saving the existing units would not preserve their affordability for very long, and in fact, the system-wide effect would be a net loss in affordability caused by suppressed supply.

Looking at the housing data by zone in the above chart, it is clear that on average, higher density development results in fewer units lost for every unit built. Given the basic math involved, that shouldn’t come as a surprise. The more housing units that get put on a given amount of land, the less likely it will be that existing housing will need to be demolished to make space for it. As can be observed through0ut Seattle, most high-density housing projects replace parking lots or spent commercial buildings, and not much, if any, housing.

Given the objective reality, it is remarkable how high density development is still so often a prime target of ire** from people concerned about the preservation of affordable housing. Instead of pushing for further restrictions and fees that impede high density development and make it more expensive, these folks ought to be advocating for policies that promote building to the highest densities wherever possible. The same goes if the concern is about preservation of open space, tree canopy, or streams. Put simply, when we build up, there’s more room leftover in the City (and the region) for other things we value.

In an analogous policy disconnect, high density projects are also the City’s biggest target for the extraction of development fees to offset their supposed “impacts.” But as the City’s own data show, the higher the density, the lower the impact on existing housing. A more sensible policy approach would place the tax burden of subsidizing affordable housing on low density properties, because inefficient land use is one of the root causes of Seattle’s affordability challenges.

The City’s ultimate example of misplaced blame is South Lake Union (SLU), which has long been a lightning rod for denunciation regarding affordable housing and gentrification. And last year SLU became the first neighborhood to be subjected to the City’s increased Incentive Zoning fees that are used to fund affordable housing. But guess what: From 2005 to 2014 (1995-2004 data were not parsed) there were 2,132 housing units built or permitted in the SLU zones, and only six housing units demolished. Not to mention the numerous subsidized affordable housing projects recently built in the neighborhood. It’s as if the City is intent on punishing the very places where things are being done right.

Lastly, none of this is say that preserving existing buildings for affordable housing isn’t one of many potential strategies that City policymakers should be exploring. However, we should not expect that the significant cost for the necessary subsidies can or should or be borne by a property owner who happens to own an old building. If the City wants buildings preserved to help meet affordable housing goals, then the City as a whole should step up and pay for it, and stop misplacing blame on housing development, which is actually part of the solution.

>>>

*For a quick thought experiment, assume that housing has a 100-year lifespan, and that Seattle built 300,000 housing units over 100 years and then stopped. At that point, the City would start to lose 3,000 units per year simply due to the lifespan of the buildings. For comparison, between 1995 and 2014, Seattle lost an average of 459 housing units per year to demolition.

**The three new “monster” housing developments shown in the King5 video that I could identify (two in Ballard, one in SLU) appear to have displaced a grand total of one housing unit!

>>>

Dan Bertolet is an urban planner at VIA Architecture and blogs at Citytank.

GMA Data: “All You Want to do is Use Me”

Bill Withers came to mind this morning as I considered how some neighborhood groups use and abuse data generated by planning agencies to implement the Growth Management Act. Here’s Mr. Withers on being used and used again:

But it doesn’t feel so good getting used when you’re on the other end of neighborhood groups that say “we’ve got plenty of buildable land, we don’t need upzones” or when they say “we’ve blown through all of our growth targets, we need a moratorium on growth!”

The truth is that the data produced to plan for growth doesn’t support either of those statements. And the purpose of GMA data isn’t to support schemes to close of the issuance of building permits but instead to actually plan for where growth will go and how it can be welcomed sustainably.

What about the first claim, “we have enough zoning.” Here’s what I wrote in a post at the Sightline Institute’ blog a few years back:

Numbers . . . are extrapolated from a subset of King County’s UGA numbers, called the Sea-Shore Subarea. This is problematic because the Sea-Shore Subarea includes two cities other than Seattle, Lake Forest Park and Shoreline, and an unincorporated area, North Highline. The Movement’s analysis of the Buildable Lands Report doesn’t make any effort to disaggregate the Seattle data from these other areas that have, in some cases, radically different land use patterns and policies. They use the terms Seattle and Seashore interchangeably.

The numbers the neighborhood groups pick in this case are distorted because they include lots of other data. Essentially their sample is contaminated and is of almost no value to support the claim they’re making. But even if we took them at their word we know that the neighborhoods oppose projects even when there is available zoning capacity. I pointed to one project that was perfectly within the zoning capacity but was killed by neighborhood opposition.

When can you move in? You can’t, because the project isn’t going forward. Neighboring single-family residents were outraged that the developers would be removing trees from the site. They rallied around the trees, organized themselves, and eventually the developer backed out. The owner of the property wound up selling the building and property to a private school. The neighborhood won and the region lost, even though the developer would have been removing fewer trees than they legally could.

The point is that no matter what the advocates of a moratorium say they’re trying to do, they’re objective is to slow or stop the development of new housing in their own neighborhoods, even if the comprehensive plan would encourage growth in their zone. Just take a look at what’s going on with the LR3 zone.

And what about the idea that we’ve “blown through” our growth targets. Here’s what a the Puget Sound Regional Council says about the purpose of Growth Targets:

The Washington State Growth Management Act (GMA) requires comprehensive, long-range population and employment planning for cities and counties. Growth targets are used to help inform this work. Growth targets — based on the state’s official growth projections — state the MINIMUM NUMBER of residents or jobs that a jurisdiction must accommodate and will strive to absorb by some future year.

Growth targets are aspirational, but must be rooted in objec- tive analysis. While they are goals for the future, targets also serve as key benchmarks against which progress can be measured, are an impetus for countywide collaboration regarding future growth, and serve as a guide for local comprehensive plans and their implementing development regulations (emphasis is mine).

Growth targets are like those mileposts you see on the side of the trail that tell you how far you’ve come; the targets never were intended to function as indicators of “runaway growth.” On the contrary, passing the growth target for jobs and housing is an occasion for celebration. But what does Jon Fox et al say about job growth, a prime indicator of our city’s economic health?

Whether they can’t afford Seattle — and many lower-wage retail and service workers now cannot — or simply prefer less-crowded suburbs, more downtown workers are putting up with longer and more hellish commutes. And adding more high-rent apartments and office space appears to be failing at reversing this trend.

There is a far better and obvious solution: Locate more of those jobs out there in the burbs and closer to where these thousands now live (emphasis mine).

It looks like the NIMBYs and their allies (organizing a big push for the upcoming neighborhood summit) have used and abused the numbers to the point that, as Mr. Withers pointed out, they are just about used up.

You’ve Heard of Backlash. Ready for Frontlash?

Frontlash is the pain that comes before big changes in a city. I can’t take credit for this use of the term,since the first person I heard use it was former Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn. He used the term to describe the neighborhood outrage and upheaval that was happening before the imposition of a “road diet,” that’s taking a four lane road, for example, and reducing it to two travel lanes with a turn lane and parking.

The purpose and effect of the road diet is primarily safety. But the projects around the city were seen as a cave in to the Big Bike lobby. There was a lot of hostility to the changes from neighbors who felt strongly that not only was the move to change the road configuration political but that it would have all sorts of other negative effects. Here’s a commenter on a blog writing about the changes proposed on NE 75th:

I feel terrible for those that lost their parking on 75th. Trying to get out of those driveways will make for dangerous conditions. Not to mention it will negatively impacts their home value. While it doesn’t affect me, I’d vote against this one. I can tell you that those who voted for this do not live on 75th. It’s not eminent domain, per se, but it sure feels like it. Just not right.

The evidence that road diets work, however, is simply overwhelming. There is no harm done and lives can actually be saved and traffic flow improved. Here’s Erica Barnett writing about how wrong the naysayers were about a road diet in West Seattle.

SDOT’s data show that the road diet has dramatically reduced collisions and reduced speeding in general on that corridor. The total number of collisions went down 31 percent after the road was striped for bike lanes and given a center turn lane, and collisions resulting in an injury went down 73 percent. Collisions between cars and cyclists went down to zero.

Now is the same Frontlash effect at work with growth and new development? Of course. Here’s a commenter talking about the pending sale of the Oddfellows Building back in 2008:

Bedford Falls continues to morph into Potterville. “Let’s evict the groups and people that make the building so vibrant, create a shallow “atmosphere” with an empty gesture toward art, jack the rents appropriately so we get an appropriate return on our investment, and move onto spread the love to the next available block!” Sorta reminds me of the nouveau riche Steve Martin in “The Jerk” dressing down a waiter- “Don’t try to sell me that OLD wine- I want NEW wine!”

Hmmm. Witty Frontlash for sure. I can’t say much except take a trip down to the Oddfellows Building now. Here’s how it was described in Seattle Magazine just a few years later:

Following the renovation of Capitol Hill’s historic Oddfellows building, myriad new shops, restaurants and hangouts have opened their doors along three hot blocks of Pine Street, between 11th Avenue and Broadway. This hip microhood is fit for both day jaunts and late-night outings; here, you’ll find the street that never sleeps.

Not much is said these days about the awfulness of the changes at Oddfellows Building. People are far too busy dancing at the Century Ball Room, eating, shopping, attending events at the West Hall, or waiting for the latest ice cream creation at Molly Moon’s. Change isn’t easy. Whether it’s knocking down an old building, renovating an old building, filling an empty lot with more housing units, or building a taller building in the LR3 zone, change makes lots of people uncomfortable.

But my guess is that most of the people wringing their hands in 2008 about the transaction and change at the Oddfellows Building and griping bitterly about the Fat Cats “laughing all the way to the bank” are fans of what’s happening at the Oddfellows Building. Or, like most of us, don’t think about it at all because it works. The Seattle City Council needs to find the same patience with Frontlash they showed with road diets for growth and new housing. Once the storm of Frontlash is over, our city will benefit with more housing choices for people of all incomes, more jobs, and more economic activity and opportunity.

The Neighborhood and its Discontents

When we start to consider this possibility, we come across a point of view which is so amazing that we will pause over it. According to it, our so-called civilization itself is to blame for a great part of our misery, and we should be much happier if we were to give it up and go back to primitive conditions. I call this amazing because—however one may define culture—it is undeniable that every means by which we try to guard ourselves against menaces from the several sources of human distress is a part of this same culture.

Sigmund Freud

Civilization and its Discontents

City Councilmember Mike O’Brien visited with the Seattle Builder’s Council on at its March meeting last Thursday morning. O’Brien said that “tensions are high” in Seattle’s neighborhoods as the city grows. Something interesting and dangerous has been going on in Seattle’s neighborhoods; the coming together of neighbors worried about the effects of new people moving into the city and what’s left of the Occupy Seattle movement. Today fear of changes that come with economic growth, new people, and the construction of housing, has merged with a social equity and justice movement. But when these two things get put together—a demand for lower housing prices and calls for no more housing—the proposed solutions are unworkable and actually hurt poor people.

When I first got involved in Seattle neighborhood work it was as a neighborhood activist and planner in Beacon Hill and South Park. Back then, in the 1990s, at least once or twice a week, you’d find me and dozens of other neighborhood people working with City staff or a consultant on ways to add to our neighborhood; traffic circles, sidewalks, road and traffic improvements, and yes, even changes in zoning to attract new development. In those days, we would sometimes bicker with the City over how long it was taking to get something fixed, but we had our eye on improvements not stopping development or growth.

We even had our challenges with developers. In 1998, Wright Runstad made a deal with the Pacific Medical Public Development Authority to move Amazon into the old Naval hospital, a prominent landmark on the north end of Beacon Hill. Here’s what I said then about the process:

My point here is not to argue the finer points of the deal. That is not the heart of the issue. The heart of the issue is trust and the role of government and the private sector in neighborhood planning and development.

As a resident of Beacon Hill involved in the neighborhood, I was disappointed in the way PacMed initially handled the deal. There was an air of secrecy, and many of us had a sense that the deal would go through with or without our support. This deal was done, and the ink was dry.

In another opinion piece in the Seattle Times called Neighborhood Voice Key in Planning, I said that the “process [of new development] should also rely on the existing network of neighborhood organizations that are active and strong all over this city.” I added that this principle of engagement “should be embraced by developers in both the public and private sector. It will save time and money.”

What a different world we live in today.

Councilmember O’Brien, Chair of the Planning, Land Use, and Sustainability Committee speaks to the Seattle Builder’s Council.

While Councilmember O’Brien was speaking with the Builders Council he made very much the same pitch I made back then. But I would never advise a builder to walk around the neighborhood and “knock on doors with cookies” as Councilmember O’Brien suggested at the breakfast meeting. The neighbors might just file a law suit or appeal! And based on stories I’ve heard from some of our smaller builders, a builder might even benefit from a body guard.

Today’s neighborhood groups are advocating things like a moratorium on growth, a shocking and unthinkable thing when I was an active neighbor. On Saturday morning I attended a panel discussion held by the Seattle Neighborhood Coalition, a group that is advocating for shutting down permitting in dozens of Seattle neighborhoods.

And Councilmember O’Brien pointed out that all the various antidevelopment and no-growth groups are banding together, something I warned him about back in 2012 when he voted against allowing some retail use on the ground floor of new development in the Lowrise 3 zone. Here’s what I said in a Crosscut article about the growing power of the no growth crowd who use Saul Alinsky style organizing to protect the status quo:

This balance of power can’t shift without courage, by developers, unions, and environmentalists who must support a louder, stronger voice for dense, transit-oriented neighborhoods, not just intellectual dialogues and power point presentations. Those advocates for better land use will have to steel themselves for more conflict with the most powerful group in the city: single-family neighborhoods.

So here we are. Councilmember O’Brien told us that the petitions and lawsuits are only just beginning, and he said, as a politician he has to listen to the opponents of growth. But the problem is that what logical outcome of merging angry, worried neighbors that want to protect their own financial investments with social justice arguments about rents being too high, is, ironically, less housing and higher prices.

This is a big reason why Smart Growth Seattle was born; the development community needs a steady, determined, and consistent voice making the case for growth in this negative environment. Mandating wage increases and stopping housing development is a recipe for disaster; that tells workers, “we pay great wages, but please don’t try to live here.” Neighbors do have power and sway over politicians (see Representative Pollet’s response to entitled homeowners), a power I suggest they are abusing. Let’s hope Seattle’s elected leaders listen to the worry, but do the right thing and the best thing to help people of all incomes moving to the city: build more housing.